Why we're failing to increase the density of our urban areas and how we can fix it

Brooklands, Sir Patrick Abercrombie, Auckland and Croydon

In 1859, cotton-manufacturer turned banker Samuel Brooks secured permission for a new railway station on the line from Manchester to Altrincham where it crossed land he had recently bought. Brooks built a new road leading to the station, allowing him to sell off large plots of land for the construction of substantial homes. Brooklands, as it is known today, is now a suburb of Manchester, the station part of the city’s Metrolink network - a factor that makes it an attractive location for commuters.

One of those original properties, Lynngarth, was home to the family of Sir Patrick Abercrombie - author of the 1944 London Plan which fathered the capital’s green belt, and founder of CPRE. Lynngarth is long gone, a cul-de-sac of eight semi-detached homes replacing it in the early 1950s. Most of the other mansions are gone too, similarly replaced by culs-de-sac of denser two-storey homes and even blocks of flats. But although the buildings have changed, the character of Brooklands – the red brick buildings either side of a wide tree-lined road, St John the Divine church standing proudly half-way along – would still be recognisable to Abercrombie.

That type of gradual change in character and gradual increase in density was once the norm - but it has ground to a halt. Attempts to replace more of the houses on Brooklands with apartments in the early 2000s prompted local opposition and a “Don’t Flat Pack Brooklands” campaign. While the details are different, the general picture is the same in most of our suburbs. They have stopped evolving, stopped growing.

The benefits of urban density are widely recognised – more efficient public transport, reduced carbon emissions and productivity gains from agglomeration, among others. Density is also key to delivering the homes we need.

Whilst we’re quite good at building tower blocks in the very centre of our cities, we’re less good at delivering mid-rise density in our existing suburbs. Over the last decade, half of our suburbs added an average of just one new home per year. We also have some of the oldest homes in the developed world - a fact which contributes to the condition of our homes being among the worst in Europe, as well as being more expensive to heat. This, too, is a consequence of our failure to redevelop existing urban areas, replacing older homes with new ones in the process.

Our planning system - and the impact it has on the land market – is a key cause of that failure.

Finding a development site in an existing urban area often involves a number of adjoining land ownerships being pieced together - two or three neighbouring houses, for example. But that is difficult, time consuming and costly.

The subjective nature of planning policies relating to the redevelopment of these sites – referring to “appropriate” increases in density or height, for example - means there is also little certainty as to what you might be able to secure planning permission for. This has two effects.

Firstly, it means developers have to allow a larger margin of error when deciding what they can afford to pay for a site. They might think they’ll secure permission for a four-storey apartment block, for example, but the price they pay for the land must be low enough for the project to still be viable if they’re only allowed to build to three-stories.

Secondly, the higher risks of successfully delivering a planning permission mean developers look for higher returns. Many of these suburban sites are relatively small, but the costs associated with securing permission for a smaller site aren’t proportionately lower than for a larger one. That increases the risk profile further.

Those effects combine to reduce what a developer is prepared to pay for the site. When sites already have buildings on them, their value with that existing use can be substantial – landowners will only consider selling if developers can offer a premium on that value. The number of potentially suitable sites is therefore reduced as a result

The difficulty, cost and time required for an uncertain return on a relatively small site, mean many developers see it as just too hard and don’t even bother trying. That is part of the reason why the number of residential planning permissions granted for smaller sites has more than halved since 2017.

That very limited supply of new homes in our existing suburbs is the result.

In the past, our towns and cities evolved gradually, with older buildings replaced by newer, taller ones as demand increased. There was slow, organic change. It’s the process seen in Brooklands. Our current planning policies have stopped that happening.

As policy is part of the problem, it can be part of the solution too. Three simple changes will allow that evolutionary process to re-start, letting our suburbs steadily increase in density once more.

First, national policy should include a presumption in favour of new development that is no more than one-storey higher than neighbouring buildings.

This goes further than current rules around mansard roofs and upwards-extensions - it should apply to the demolition and replacement of a building, or groups of buildings. If a developer can buy three or four neighbouring properties, it should be possible to replace them all with a single apartment block that is no more than one storey higher than the neighbouring properties that remain. This will allow a slow, step-by-step increase in building heights and densities over time. The character of an area will gradually evolve, rather than changing in a dramatic, step-wise way.

Second, national policy should include a presumption in favour of six-storey development in areas within 500m of a railway, underground or other light rail stop. This would ensure that the densest development is delivered in the most sustainable locations.

Third, local authorities should be encouraged to use design codes to identify other areas where an increase in density is acceptable. This would include discrete areas within existing suburbs - perhaps close to a neighbourhood centre or along a main arterial road, for example. The design code could be used to specify the height and density of development that would be acceptable.

When local authorities opt to do this, they should be allowed to make reasonable assumptions about the number of new homes that will be delivered as a result, and count that anticipated construction towards the housing target in their Local Plan – a clear incentive for them to plan for density increases.

Taken together, these three changes will increase certainty as to what form of development would be acceptable, encouraging developers to proactively seek out suitable sites - including committing the time and money to piece together multiple land ownerships.

Many of the sites delivered by these changes are likely to be smaller, suitable for SME developers and helping reverse the decline in the number of small sites granted planning permission.

The changes to national policy can be introduced quickly as part of the government’s “Brownfield Passports” initiative1 - and would have an immediate impact, contributing to the target of delivering 1.5m new homes over the next five years.

We know policies like this will work. For example, similar changes in Auckland, New Zealand – including allowing six-storey buildings within walking distance of rapid transit stops and city centres - saw an increase in the number of new homes built, and a fall in rent levels compared to the rest of the country as a result. They were so successful, similar reforms have since been rolled out more widely across New Zealand.

And we’ve already seen it work in England too.

In 2019, Croydon Council introduced a Suburban Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document, with the express aim of allowing the “evolution of the suburbs to provide homes that will meet the needs of a growing population.”

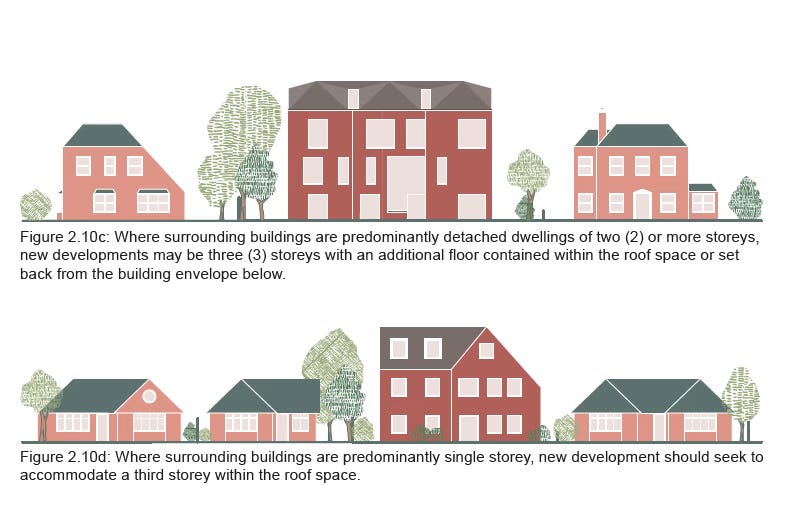

The guidance covered smaller scale schemes across the whole borough, setting out where storey heights could be increased, and where infill and back-land development would be acceptable.

More detailed guidance was provided for four “Areas of Focussed Intensification” – centred on existing transport hubs and shopping centres – where even greater density increases would be allowed. This was all to be achieved in a way that was sensitive to the suburbs’ existing character. A huge number of illustrations and photographs were included in the guide, making it easy for developers to understand what was expected of them.

The number of new homes built in small developments tripled after the guidance was introduced – and before it was revoked by a newly elected mayor.

By setting clear expectations for developers, these simple changes would allow the traditional evolution of our towns and cities to re-start, improving the quality of our built environment and housing stock and increasing the density of our existing built-up areas at the same time as helping deliver more of the homes we need, in the locations that they are most needed.

We need to let Brooklands – and suburbs like it – live again. Something Abercrombie would surely have agreed with.

Which looks very like a name in search of a policy, at least for now.