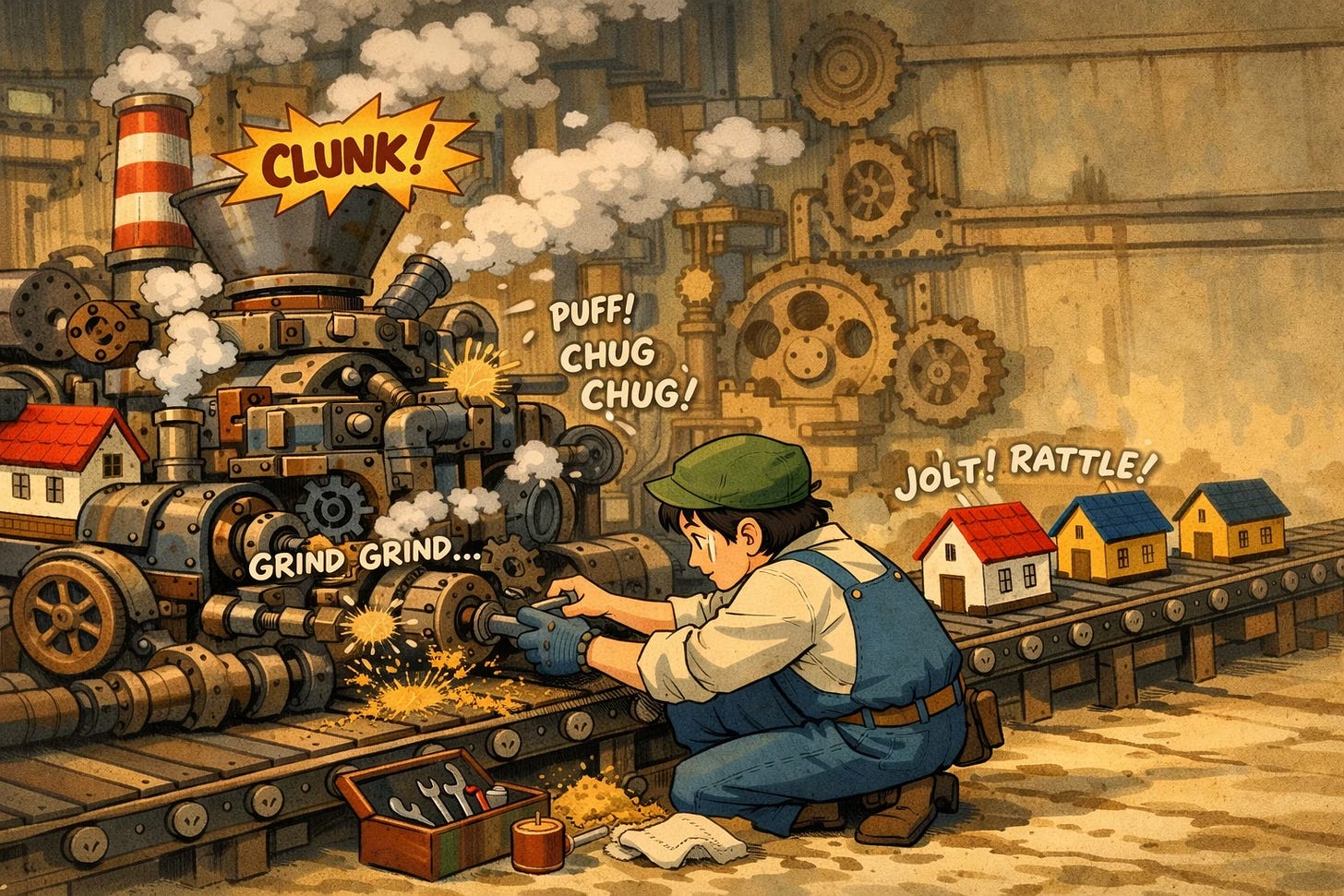

Removing grit from the planning system and speeding up the process

Our planning system is clunky and slow. Here are some process changes that could help speed it up.

England’s planning system is incredibly slow. On average it takes two years to determine a major1 outline application for new homes. And because that’s the time from formally submitting the application to the council, it doesn’t include the period spent preparing the application and engaging in the pre-application process.

That’s one of the reasons why the changes to the planning system introduced by the Labour government to date - essentially the introduction of grey belt and mandatory housing targets - have yet to show up in either the number of homes granted planning permission or being built.

It also means that we’re already at a point where further systemic reform is unlikely to have an impact before the next election.

While many will argue delivering more homes means fundamentally changing the existing planning system, there’s still plenty that can be done to remove grit from the system and really make it hum, delivering more homes, more quickly.

Flood risk policy provides an example of how effective this can be. The way planning policy operated slowed down applications and increased costs without delivering any improvement in outcomes. Research by industry body the Land, Planning and Development Federation indicated that applications for as many as 100,000 homes were being delayed. So the government acted, making relatively modest policy changes which removed that barrier to development overnight, without reducing the quality of development, or increasing the risk of flooding (in fact, the new approach probably reduces the risk of flooding).

Speak to anyone involved in the planning process, and they will very quickly identify many other examples of grit in the system that the government could remove relatively easy and speed up the process without having any impact on the quality of permissions granted.

Here are some examples, all aimed at ensuring we hit the government’s home building targets, and arranged roughly in chronological order through the application process. They are all intended to be about process, not policy while initiatives the government is already working on - like a national scheme of delegation and a new “medium” site size category - have deliberately been ignored.

Although this list barely scratches the surface, it is long enough to make sure there will be something for everyone to hate. Take the ideas you like and make them better. Ignore the ones you think are crazy. Please do leave a polite version of your thoughts in the comments.

Fix the pre-application process

Developers are told that pre-application discussions are the key to a quick application, as issues can be resolved before the application is submitted. But moving some of the planning work from the regulated, measured process of a formal application to the unregulated, unmeasured one of pre-application doesn’t actually speed the process up - it just flatters the statistics.

The quality of pre-application responses is highly variable and all too often only partial. It is common for statutory consultees and council officers from other departments not to provide any input at all. The level of planning gain is rarely confirmed, making it virtually impossible to reflect in the land value. Local authorities can take as long as they like to organise meetings or issue written responses.

When they arrive, those responses aren’t binding on the council. They usually finish with a disclaimer along the lines of “we reserve the right to change our mind for any reason at any time.” Sometimes that change can be nothing more substantial than a new case officer.

This service is becoming ever more expensive - fees for pre-application advice can be as much as £20,000 or more even for relatively modest proposals in some authorities.

A better approach would be to treat written responses like a Statement of Common Ground used in the appeal process.2 Based on the information provided at pre-application stage and the policy position at that time, this would set out what the council and the applicant agree on, what they disagree on, and what further work is needed. Once that’s done, neither party can change their positions - unless the facts of the application materially change - providing certainty for everyone.

The detail in these statements will depend on the detail provided by the pre-applicant. For example, if there is a Transport Assessment, it might say that the Assessment is accepted and the highway network can accommodate the scheme provided an agreed list of improvements are delivered. If there is no Transport Assessment, it could only say the parties agree that one is required.

Performance at the pre-application stage should be measured. Local authorities should be required to publish how long it takes to provide a pre-application response allowing the government to monitor and benchmark performance.

Abolish planning performance agreements

The original logic behind planning performance agreements was sound. Application fees didn’t cover the costs of processing many large-scale applications, so applicants could pay more in exchange for the planning authority committing to performance targets.

The reality has been somewhat different.

Councils have been understandably reluctant to agree to fixed targets when the time it takes to determine an application isn’t wholly within their control - it depends on third party consultees and even applicants themselves - so performance agreements have become little more than another way to raise money. At the same time, they add delay and uncertainty while they are negotiated and signed.

Now application fees can be increased to cover the actual costs of dealing with an application, there is no case for performance agreements to remain. Abolishing them will give planners one less thing to do, and strip out a point of discussion that can slow the application process.

Be brutal about what information is required to support applications

The national schedule of validation requirements - which set out what must be submitted as part of an application - should always be enough. The information submitted should be directly relevant to the nature of the application, with a laser-like focus on what that actually means.

For example, outline applications are supposed to establish the principle of development, not the detail so they really shouldn’t need to include a layout. If an outline application is made for “up to 100 homes” but then, at reserved matters stage, only 70 homes can be accommodated on the site whilst achieving an appropriate layout, then only the 70 home design would be approved. “Proving the coverage” at outline application stage should be irrelevant.

Many other supporting documents are insisted upon at outline stage which don’t go to the heart of the principle of the proposed land-use. One authority requires applicants to survey local residents to determine what size homes they may require before submitting an outline planning application - which doesn’t even decide the mix of housetypes.

Applications for smaller sites should have different requirements too. Can a scheme of 50 homes ever result in the loss of enough farmland to justify an agricultural land quality assessment, or be enough of a visual blight to ever need a landscape and visual impact assessment?

Stricter time limits on public consultation responses

Whilst there is a formal consultation period of 21 days at the start of the application period, in practice comments from local residents are considered whenever they are submitted. As a result local authorities ask for changes to schemes late in the application process based on new resident concerns.

Whilst some layout changes may seem minor, the time implications can be large. Delete a short section of footpath, for example, and the layout, landscape design, engineering design and even the street scenes might have to change. That’s weeks of work and thousands of pounds of cost.

There are few other regulatory regimes with such open ended consultation periods. Even the planning appeal process has rigidly applied deadlines.

Of course, no one is saying the local communities shouldn’t be consulted - but they should have a defined window to respond in. If you think 21 days isn’t long enough for communities to consider an application and provide a response, then make it 28 days. Make it 35 days even. But limit it. Comments submitted after that cut-off should be disregarded.

If, later in the process, the scheme changes significantly then the local authority can - at their discretion - choose to consult the public again on those amendments.

That still gives local residents a fair opportunity to comment, but provides applicants a fair chance to amend their schemes too.

Streamline the issues planners are expected to deal with

Each new government initiative seems to load work on to the planning system without anything ever being taken away. Some of the matters planners are now asked to deal with shouldn’t be the responsibility of the planning system at all, especially where they are covered by other regulatory regimes.

We don’t expect planning officers to deal with building regulation compliance, nor do we impose planning conditions that require compliance. Why, therefore, do we expect the planning system to deal with the technical approval of drainage designs or remediation strategies, for example? Why can’t applicants deal with the approving bodies directly (the water company and the environmental health officer in those examples), instead of expecting planning officers to sit in between the two, forwarding on emails?

Nutrient and water neutrality have become planning matters solely due to the failure of other regulatory regimes. Construction Management Plans deal with issues covered by Environmental Health regulations. That shouldn’t be the planning system’s concern.

It doesn’t matter if we think those other enforcement regimes are doing a bad job - it isn’t for the planning system to fix it. Planners should be directed that issues covered by other regulatory regimes are not a material planning consideration, and that they should assume those regimes are working correctly.

Standardise S106 Agreements (or abolish them altogether)

Section 106 agreements - which secure both affordable housing delivery and financial contributions from developers - are taking longer and longer to finalise: months or even years. Without them planning permission can’t be issued and development can’t go ahead.

A nationally standardised Section 106 agreement would dramatically speed up the process. Instead of lengthy negotiations over operative clauses - how long do the council have to spend the money and should there be an affordable housing cascade? - those parts could be standardised. Local councils would be left to complete little more than the site address, level of contributions, precisely what they are for, the payment profile, and the mix, tenure and plot numbers of affordable homes.

This is such a good idea, that planning law firm Town Legal took it upon themselves to coordinate the production of a draft template. The government have said they will introduce a version of this, but are still saying it will be a “starting point” for local authorities. That means councils either won’t use the template, or will change it. If a template is going to be introduced, its use should be mandated.

Better still why not abolish Section 106 agreements altogether? The vast majority of planning gain requires a financial payment. We should be able to detail the sum, and its purpose, as a condition on the planning decision notice (with the added benefit of providing greater transparency).

The complexity of affordable housing delivery means it would probably still need to be managed through a Section 106 Agreement (perhaps re-branded as an Affordable Housing Agreement) but basing this on a national template would still serve to speed the process.

Planning appeals with main modifications

If a planning inspector examining a local plan decides it isn’t compliant with national planning policy and law,3 but can easily be made so, they don’t simply throw it out – they ask councils to change the plan so they can allow it to be adopted. The same principle should apply to planning appeals.

If an appeal scheme isn’t acceptable but can simply be made so, inspectors should be able to request that applicants make those changes before determining the appeal, rather than dismissing the appeal and requiring a whole new application process (with the extra time and cost that involves) before the scheme is finally approved.

Giving tight timescales to make those changes - to be set at the inspector’s discretion depending on the issues involved - means appeals won’t drag on and that the process overall will be sped up.

This list is far from exhaustive. Other will have many more ideas like this too.

For a start, here are some from the excellent 50 Shades of Planning Blog and MHCLG’s own recent report on “Delays and barriers experienced in the planning application process” should also give you plenty to think about.

Leave your own suggestions in the comments.

These might not be especially big schemes - in planning terms, anything of 10 homes and upwards is classed as major.

An idea shamelessly stolen from Andrew Taylor of home builder Vistry.

“Sound” in the planning jargon.