There’s a new obstacle to the government’s home building target: puddles.[1] Or, in planning jargon, “surface water flood risk”.

What planning policy says about flood risk

There’s a lot of planning policy dealing with flood risk - twelve paragraphs of the National Planning Policy Framework (roughly 5% of the total) and more than 20,000 words of practice guidance. And that’s before you get into the additional guidance provided by the Environment Agency (EA).

That’s understandable. Nobody wants their home to flood. Making sure new homes aren’t likely to flood and don’t make flooding more likely elsewhere is hugely important. No one would dispute that.

For housing development, those policy requirements can be boiled down to a few simple rules. Homes should ideally by built in locations with the lowest risk of flooding. Built development - which means not just new homes but also “access or escape routes, land raising or other potentially vulnerable elements” - should be kept outside areas at risk of flooding. If only part of a site might flood, those areas should be used for “less vulnerable” uses, like open space.

If built development is proposed in an area thought to be at risk of flooding either now or in the future, it should only be allowed when it can be shown there aren’t alternative sites with a lower flood risk. The process for demonstrating that is called the “sequential test,” and can be carried out by councils when they prepare a local plan, or for individual planning applications.

If a site passes the sequential test, the proposed development must be made safe from flooding for its lifetime, and without increasing the risk of flooding elsewhere.

How housing developments deal with surface water

Before getting in to what those policies mean in practice, it is worth taking a moment to understand how surface water drainage is dealt with in new housing developments.

Surface water flooding occurs when there has been so much rainfall that drainage systems are overwhelmed. Those drainage systems can be man-made - like surface water sewers or drainage ditches - or more natural, like rainwater simply soaking into the ground. Rain falls whether we build homes or not, so every piece of land already has some way of dealing with that surface water. If the existing drainage system isn’t very good, you might even get some big puddles.

Building homes inevitably changes how those drainage systems work. For example, it introduces a series of impermeable surfaces - like roofs, roads and driveways - which increases run-off - the speed at which rainfall enters watercourses.

In the course of construction, developers will almost always change a site’s ground levels too. That’s for a whole range of reasons: to ensure new foul sewers can drain by gravity; to allow material excavated from foundation and sewer trenches to be kept on site rather than taken to landfill; to make sure the roads and paths serving the new homes aren’t too steep. By the time all that work is done, the low points - where puddles might form - are in different places.

The dynamics of surface water drainage on the site are fundamentally changed. Developers take all of that into account when they design a surface water drainage scheme regardless of the prior risk of surface water flooding.

They will use a combination of the gradient of the land, drainage ditches and pipes to direct rainfall to a storage area - usually a pond or storage basin, but sometimes an underground chamber - from where it is slowly released into a nearby watercourse or surface water sewer at a rate that won’t increase flood risk. Less often, and if the ground conditions are suitable, the system is designed to allow the water to slowly soak into the ground.

Even with all those new impermeable surfaces, the rate at which water flows into watercourses or soaks into the ground is restricted to make sure it is no faster than would have happened before the homes with built. That help makes sure the new development doesn’t make flooding more likely elsewhere.

The surface water drainage system is also designed with enough capacity to deal with all the rainfall likely to fall on the site, plus a generous allowance for the wetter weather we’ll experience as a result of climate change. The EA have 3,200 words of guidance on what that allowance should be. The drainage scheme even needs to reflect the fact that some future homeowners will replace their gardens with parking areas, paving, or astroturf.

This approach reduces the risk of flooding from surface water both on site and in the wider area, compared to the development never having taken place. Remember, the drainage scheme is designed to safely deal with the higher rates of run-off caused by the development, plus changes the new residents might make in the future, plus increased rainfall from climate change.

How flood risk planning policy is now being interpreted

Enough engineering. Back to planning policy, and how it is being interpreted.

Surface water is only one potential source of flooding - there are lots of others too. Rivers can burst their banks. The sea can overwhelm coastal defences. Dams can breach.

Flood risk planning policy was always assumed to refer to the risk of flooding from rivers and the sea. It’s hard to move a river, or change where river water goes if it overtops its banks. The sea is even more difficult to manage. The EA publish a “Flood Map for Planning” which, until this year, divided England into three zones based on their chance of being flooded from just those sources.

Surface water flooding is functionally different from flooding from rivers and the sea. Rain falls evenly across a whole site and will run towards the lowest points. Those lower points will change as a result of construction, and surface water drainage is actually improved by new development.

So, while flood risk from rivers or the sea needed to be designed around or subject to the sequential test, surface water flood risk was simply dealt with through drainage design. Everyone seemed content with that approach.

But then a change to the Planning Practice Guidance and a series of appeals and court judgements[2] revealed developers now had to deal with surface water flood risk in the same way as the risk of flooding from rivers. To compound matters, in December the EA updated their surface water flood maps dramatically increasing the areas at risk of flooding from rainfall - the number of existing homes at risk increased by 43%, for example. Then, in March, surface water flood zones were added to the Flood Map for Planning.

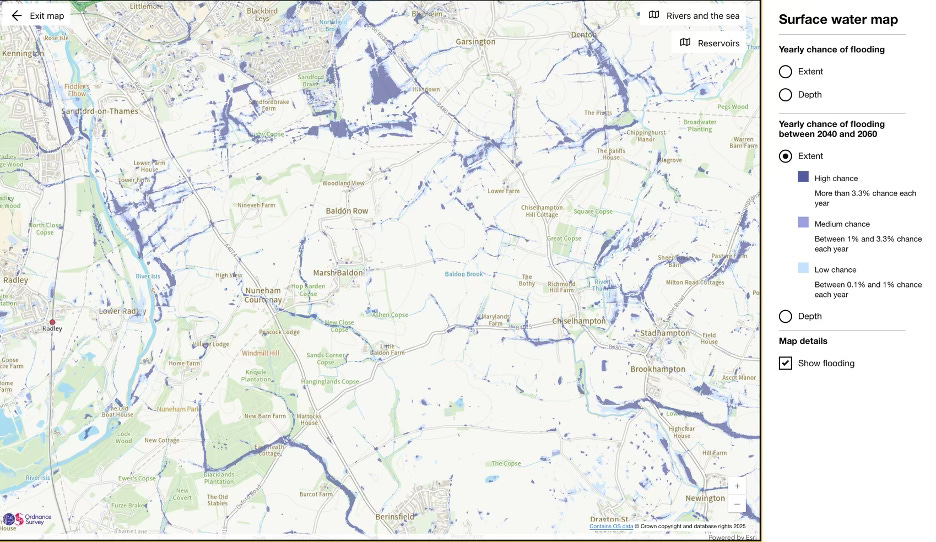

Look at any part of the country, and you’ll see it is pockmarked with potential puddles. Here’s an extract from the surface water map chosen at random, but take a look for yourself.

These maps aren’t entirely accurate - it’s hard to predict where puddles will form on a national scale. As the EA themselves state: “The climate change and depth scenarios shown on this map may help to inform risk assessments. Further assessment is likely to be needed to assess planned development.”

But they are all local authorities have to go on, so if they show a puddle might form on part of your site, you must deal with the entirety of flood risk planning policy.

The practical impact on housing development

If those maps show possible surface water flooding on a site, developers have three options.

The first is to go through the sequential test and prove there are no other sites at a lower risk of flooding which can accommodate the development instead. That’s harder than it sounds. Your search for alternative sites needs to cover the entire local authority area, even if the development is meeting a very local need.

The sequential test must also consider both smaller parts of larger sites and combinations of smaller ones that could deliver the same number of new homes.

And there is often lively debate as to whether a site is actually available for development. What if the landowner has no intention of selling? Should the site be taken int account anyway?

Depending on the size of the council area, you will need to pay a consultant £20,000 or more to carry out that sequential test, and even then, the council might not agree with it.

The second option is to produce your own surface water flood model of the site. The EA’s map is based on fairly crude data and a host of assumptions, so a site-specific assessment might show the surface water flood risk in different locations. That process is expensive - £15,000 to £20,000 for even a modest sized site. It’s slow too, taking 4 or 5 months, in part because you need to get the EA to approve the model at various stages. And there’s no guarantee the answer will be much different.

The third option is to design your layout around those potential puddles, using them for open space instead, for example. In some instances that will be easy to do. In others, the areas of surface water flood risk will be in awkward locations impairing both design quality and the efficiency of the layout, reducing the number of homes the site can accommodate.

As the level of those areas can’t be changed - that counts as built development and would trigger the sequential test - they will be low points collecting water forever. If you’re unfortunate enough to need to access a site through an area of surface water flood risk, development simply might not be allowed - even if the puddle wouldn’t be deep enough to cover the new road.

All of this might be justifiable if it protects us from flooding. But it doesn’t - it’s worse than the previous approach. The planning system is now asking for housing developments to be designed around puddles that may or may not be in the right place on a map; to carry out expensive, time-consuming modelling to prove the map is wrong; or to try to find sites on the other side of the borough which might have fewer of the hypothetical puddles.

What isn’t acceptable is simply designing a drainage scheme that takes rainfall and surface water flood risk into account while making the situation better for new and existing residents at the same time as providing extra capacity for heavier rainfall in the future.

As a result, development is slowed or stopped altogether - or the number of homes being build reduced - across the huge number of sites that are hypothetically at risk of surface water flooding, for no discernible benefit.

Some real examples

This is already producing odd outcomes.

In a recent appeal[3] for 644 new homes on a site that had already been identified for development as part of a new Garden Village, the Planning Inspector noted that “flood risk mapping is generally seen in a two-dimensional perspective. It covers a particular defined area and does not take account of height. So even if a road is elevated and a bridging point provided over a culverted watercourse, it is still located within an area of flood risk.”

She went on to note that “I acknowledge that the proposed surface water drainage strategy has the potential to result in betterment. It is proposed to regulate surface water run off flows through the use of attenuation basins and tanks so that run off will be attenuated on site up to and including the 1 in 100 year plus 50% climate change event. This would have post development benefits as it would reduce peak flows which contribute to existing flooding downstream and ensure the development does not increase the risk of flooding elsewhere.”

Despite that, the developer’s failure to undertake a sequential test - for a site that formed part of a Garden Village, remember - was the “overriding consideration” in dismissing the appeal.

Similarly, an appeal for 34 accessible bungalows for older people[4] on a site with some surface water flood risk was dismissed because the developer had only looked for alternative sites within a 5-mile radius of the application site. You might think, quite reasonably, that if you’re moving into that type of specialist accommodation you probably want to stay near your existing social networks and have visitors from time to time. But the Inspector dismissed the appeal because the developer hadn’t considered whether there might be sites on the other side of the borough - as much as a 40-minute drive away - where puddles were less likely.

How it can be fixed

The good news is that this is all really easy to fix with two changes to national policy.

Make it clear that surface water flood risk should be taken into account as part of the design of drainage schemes but that it isn’t a trigger for the sequential test.

Make it clear that the sequential test only applies to the settlement in which the development is proposed, rather than the whole authority area.

Two simple changes that would not only allow more new homes to be built more quickly, but produce better outcomes for flood risk too.

Without those changes, home building will be slowed or stopped as developer’s deal with sequential tests or flood modelling and design quality will be compromised as layouts seek to avoid areas within sites where puddles might form. Neither are outcomes the government can afford.

[1] Yes, yes. I know it’s more complex and nuanced than puddles. But also, it really isn’t.

[2] Zack Simons has written a typically good summary of the original judgement.

[3] Appeal reference APP/A2335/W/24/3345416

[4] Appeal reference APP/P2365/W/24/3350235